Very quickly you establish a familiar rhythm to life in hospital: wake up, check vitals, answer questions, breakfast, call Suzy, shower, stretch, rounds, more questions, nap, lunch, vitals, listen to music, nap, session with a therapist, Suzy’s visit, dinner, nap, vitals, lights out.

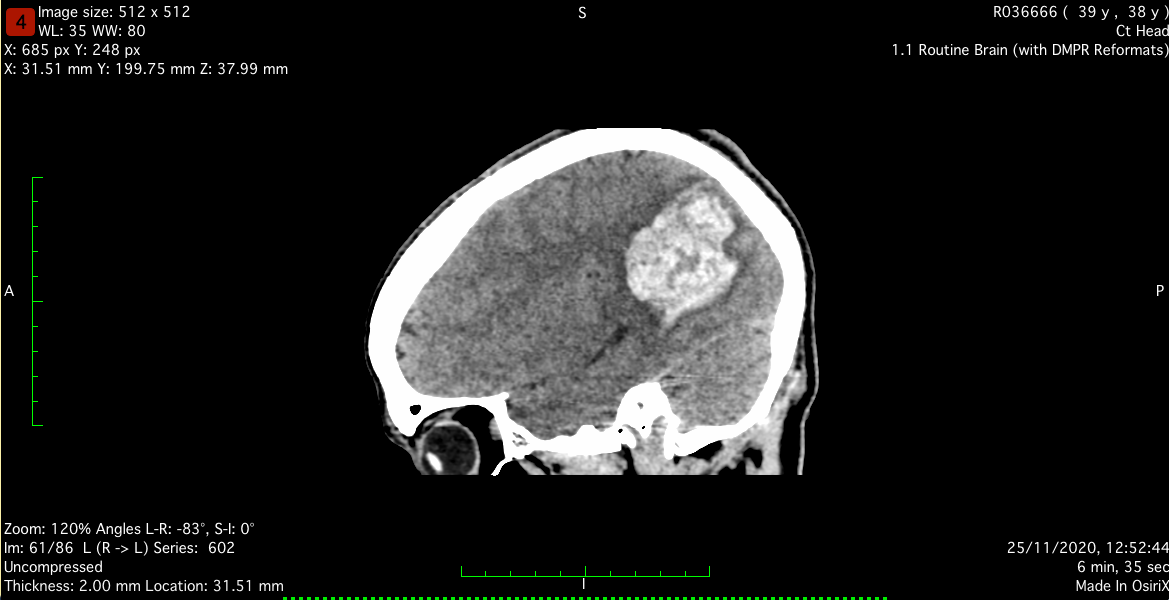

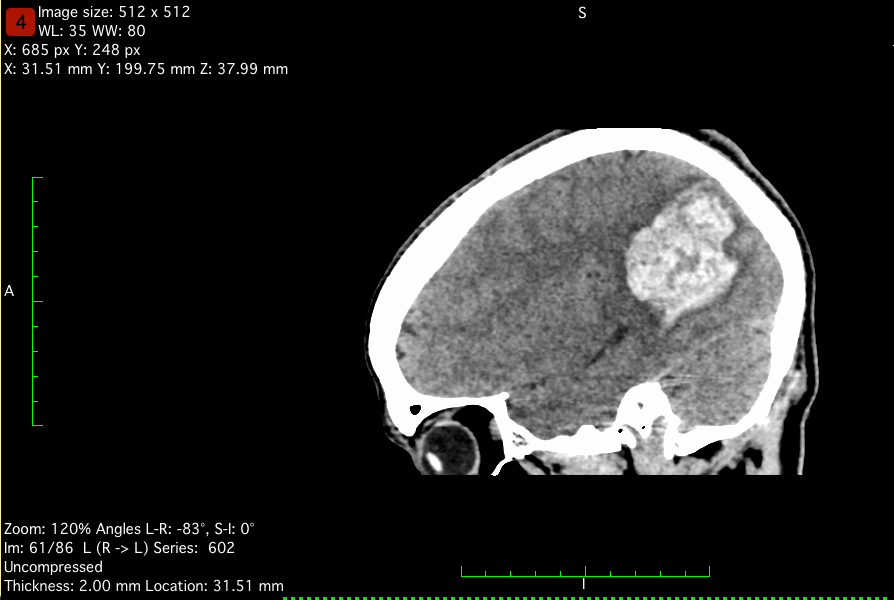

Although all of these tasks became routine, the disconnections in my brain caused me some challenges, regularly leaving me confused. Just taking a shower took real concentration. I’d set up the different items I’d need in order, otherwise I’d just stare at them unsure what to do next. Furthest from the door, I’d lay out the shampoo and shower gel, then on the sink, the beard trimmer, toothbrush, toothpaste and moisturiser, finally safely on the toilet seat, fresh towel, gown and flight socks. I discovered that if I lay each of these items out in order, then I’d know what they were for, but if I was searching for something, then I wouldn’t be able to recognise it. Part of the problem was my eyesight, but it turns out I was also suffering from aphasia, caused by the damage done during the bleed. The haemorrhage had affected the left side of my brain, which controls language, speech, logic and organisation. I recognised speech, thoughts and meanings but when I returned to the place in my brain where I stored them, they were no longer there. It can be as frustrating as losing your keys, knowing they can’t be very far away, but you just can’t seem to put your hands on them. Now that I was engaging with so many more people, it became obvious. I imagined that the words had been swept away by the blood, and they were now floating dislodged from their homes. Mostly I’d be able to scoop up the ones that I wanted, but occasionally I’d have to pick up and use whatever word was closest to me. My brain would give me access to language that felt similar, or that allowed me to describe what I meant. I’d say things like, ‘what’s for early morning dinner’, meaning breakfast, and ‘my feet wrists are a bit swollen’, instead of ankles. One of my favourites was during a procedure to map my brain, when asked to identify a picture of a duck, I said ‘oh yes, it’s a wet chicken’. The aphasia intensified when I was tired and the words would feel like they were deliberately hiding. I could taste what I wanted to say, the words swilling around the tip of my tongue, just not close enough for me to spit them out. Recently it was described to me perfectly by a speech and language therapist, he said aphasia is like getting a new assistant, but they’re not very good. They keep filing things in the wrong place and moving the folder you were working on, often giving you different items to what you’d asked for. Laying out the bits and pieces in the shower meant that I didn’t have to search for the words and meanings every time. Which allowed me to concentrate on not falling over.

After the shower I’d steady myself next to the bed and do some gentle stretching. Most of this year I’d spent working as a gardener, and so being stuck inside and horizontal was taking some getting used to. I joked with the nurses that I might try and find a local zumba class, for now I’d have to settle for some hospital aerobics. Completely straight faced, I’d attempt to look as ridiculous as I could while moving my gangly body around, any excuse to entertain, pirouetting, lunging and contorting as if I was slightly possessed. Attempting to make my roommates and the staff giggle. I’d explain that these were vital rehabilitating stretches, encouraging Juan and the current occupant of the fourth bed to join in. They’d mostly look at me concerned about my wellbeing, but one morning Adam, the latest recruit, decided to get involved. We added some eighties classics and suddenly we were having a dance party. Adam, Juan and I escaping from our current predicaments, wiggled, shook and gyrated for the next hour, free again for a moment, happy to be alive. Nurses from right down the corridor appeared at the door, probably assuming that they’d mixed up our meds. I’m not sure how they explained the sudden spike in our vitals, but we all slept pretty much the entire afternoon.

Getting through the daily routine of hospital was made so much easier by the incredible outpouring of love I received from my family and friends. It had clearly been a shock, and I’m very sorry I had put them through it. Over the past ten years I’ve helped run a summer camp for teenagers, and on the few occasions they were to be taken to hospital or had fallen ill, I noticed the stress levels of their parents halve as soon as they heard their child’s voice. If I initiated the call minds would race to the worst possible situations, but if the student phoned directly everything would be ok. From my first few hours in hospital this became an obsession for me. Just after I arrived into the high dependency ward, dazed and confused I told Suzy that I needed to inform my parents about what had happened. She said to rest and she’d tell them when she got home, but I insisted I called and that she could then fill in the gaps. My sister was visiting them and it was a relief to know they were all together. It was undoubtedly still difficult to hear, I’m just glad I got to be the one to tell them. As the news of what had happened spread to my friendship circle I started to receive overwhelming messages of love and support. These became daily deliveries of energy, encouragement, and hope. I received recordings from friends and their little ones reciting jokes, there were messages in character, my friend Elliot did a different accent every day, love arrived from all over the world. It was incredibly touching to hear everybody’s concerns. As soon as I felt up to it I made sure that everyone had an opportunity to hear my voice. I recorded clips, to reassure people that I was going to be ok. Listening back to the earliest recordings, they’ve formed a time capsule. I’m shocked at how different my voice sounds, it’s slow and unsure like I don’t know what’s about to come out of my mouth. I remember trying to make myself sound as positive and enthusiastic as possible, I thought I was fooling everyone, but my voice was clearly betraying me.

I’m enormously grateful for all the continued support.

Both Suzy and my family made me feel like the decision of what to do next was mine. I’m very grateful to them for this; although I’m sure they had strong opinions, they ensured that I felt supported and in control. I decided that even though it was the riskiest procedure, I felt confident in Dr Kailaya-Vasan and I opted to have the AVM removed during brain surgery.

I didn’t want to face five years of walking on eggshells, unsure if I’d have another bleed, worried about every stressful situation, too much excitement, or an accidental bump to the head. My time in hospital contemplating how lucky I had been made me eager to make the most of every moment. Pausing life for the next five years didn’t feel like the right choice for me, for our family, or my future. It was on my 39th birthday that I signed the consent form for the operation. To be fair they offered to come back the following morning, but somehow it felt like this was the perfect moment. Ben, a colleague of Dr Vasan talked me through all the risks and made sure I understood what was going to be happening to me. If I’m honest I didn’t comprehend the enormity of what lay ahead, brain surgery just felt like the next hurdle in my goal of getting back to life with Suzy. Surviving the rupture had been a miracle, it was life-changing and irrefutably altered the way I now approached the world. Looking back I’m shocked at how brave and certain I was about consenting to the procedure. It’s extremely possible that I was signing my life away. Choosing to go under the knife felt at the time like my only real option, the outcome however would be fifty/fifty. Either it would be completely successful or not, and if it wasn’t then who knew what my future would hold.