It must have been almost midnight, as the panicked alarm on the ECG squealed next to my bed. Earlier that evening they’d managed to move me upstairs to a room in the high dependency unit. Still awaiting the results of a Covid test, I’d been placed in isolation. Some of the nursing staff turned a blind eye and Suzy had been allowed to stay with me until almost nine o’clock. We’d held hands as she watched and I listened to the final of the Great British Bake Off. It was a welcome distraction, and stopped me from asking what had happened over and over again. After the shift change a night nurse told Suzy I should get some rest and it was time for her to leave. As the lights dimmed I suddenly became aware of how exhausted I was, almost immediately I was fast asleep.

The ECG had started playing up a little because my blood pressure was low. From twelve onwards, the alarm and accompanying headache ensured a restless night. Alone with my damaged mind I attempted to make sense of it all. Loops of thought battled through the blood-filled pathways of my brain. Family and friends, Suzy, performing, health, wealth and everything else took turns to reintroduce themselves to my misfiring neurons. I spent a few hours reciting Shakespearian monologues, equally delighted they were still in there and terrified they’d soon disappear. At 4:52 am I attempted to take a selfie, convinced that part of my face had dropped. I squinted at my blurred, pulsating image, unable to know for sure.

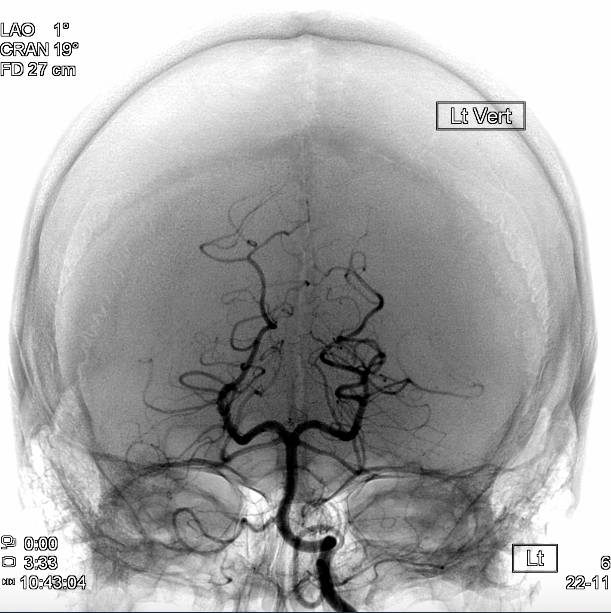

The next morning I had to attend an angiogram; the lack of sleep added to my confusion and the shaky vision made me nauseous. I lay on a cold metal table as the nurse explained that a local anaesthetic would prevent any pain, but that it might be uncomfortable. She then removed my boxers, and started to shave my groin. The doctor inserted a needle terrifyingly close to my right testicle and then threaded tiny tubes and wires up through my body to near my brain. Surely there’s a more direct route, this can’t be the easiest way? She injected iodine dye and a metallic taste filled my mouth. Above my head I could see the black and white images of my blood vessels dance and flicker on the screen, it reminded me of wispy smoke rising out of an ashtray. Later I discovered that the procedure had been looking for an aneurism, instead what they confirmed was an AVM – Arteriovenous Malformation. Without getting overly technical, an AVM is an abnormal entanglement of blood vessels between arteries and veins. It affects less than one percent of the population and most likely had been with me since birth. It causes the tangled blood vessels to bypass tiny capillaries allowing high-pressure blood to shunt directly into my veins from my arteries. Like a ticking time bomb it eventually caused a rupture near my parietal/ occipital lobe, and the brain haemorrhage restricted oxygen and caused the stroke. Statistics of death caused by ruptured brain AVM’s don’t make for easy reading. I had been very lucky, and although we now felt better because we had a cause, there was still a chance I could bleed again.

The next two days in hospital were by far the worst of my entire life; fatigue, confusion and agonising pain were my main companions. Morphine, fentanyl and paracetemol took turns knocking me out every few hours. I was unable to keep anything down, often waking up while vomiting on my bed sheets. Being unable to see made me dizzy and disorientated, adding to the thick fog clouding my mind. Through all of it I was comforted by some of the most wonderful people I’ve ever met. In between the hour a day that Suzy was allowed to visit, I surrendered to the medical staff. Driven solely by the fact that it’s their job could only have taken them so far, the rest was pure devotion, empathy, and kindness. These angelic lifesavers dived in every time I slipped under the surface, going far beyond what was necessary. I cannot thank them enough.

The nights on the high dependency ward were the most difficult. Lying flat made the pain worse, and the patient next to me would scream as she experienced hallucinations. At first she was convinced that a cat had climbed in through the non-existent window, she would shout for the nurse as she spotted it scurry under her bed. Later, unprovoked, she thought that someone was attacking her, for hours she squealed ‘no, let me go, don’t touch me’. The nurses would calmly attempt to reassure her, but she’d just turn on them. I felt helpless; she was clearly distressed, and part of me was terrified that in a few days time that would be me. I decided to be extra nice to everyone just in case it was.

At this stage the doctors were unsure if my vision or memory would recover. The plan was to monitor me for a couple of weeks until the blood in my head could be re-absorbed by the brain.

After a rough start, by the morning of the fourth day I had started to feel much better. Ansy, the most wonderful nurse, had spent the morning making me laugh and teasing me at how often I wanted to brush my teeth. After breakfast the doctor and around fifteen students would do rounds, usually I’d just lie there barely conscious, unsure what to say. Today however I sat up and smiled at them all; even though I was unable to see their faces, I wanted to show them I was on the mend. After the usual set of questions, name, date of birth, I always got those two correct, I’d guess at the rest.

‘Can you tell me where you are?’

‘Yes, I’m at Kings Cross St Pancras’

‘No that’s a train station, we’re at Kings College Hospital.’

‘Oh’ I’d say, unconvinced.

‘What year is it?’

I racked my brain, convinced I knew this one.

‘Is it 1997?’

‘No, try again’, said the Doctor, like a surly teacher.

‘That was a good year’. I deflected.

‘It’s 2020, Mr. Clegg’.

‘That’s a bad year’ I said, feigning horror, causing a few students to laugh.

I’d been asked these questions every three hours for the past few days. I knew the answers were in there somewhere, floating around, I just couldn’t reach them. Today’s doctor seemed aware that I was enjoying having a crowd.

‘Can you tell me who the Prime Minister is?’ he asked, throwing me a curve ball.

A new question, come on brain! I focused, and searched every possible corner of my mind, after a while I shook my head and said, ‘Sorry, I’m not sure, but I know he’s a massive prick.’

It brought the house down; the doctor stifled a giggle as the students and nurses behind him cheered. Grinning from ear to ear, I’d never been more proud of my addled brain. Somehow I’d managed to perform again and I didn’t want it to end. I couldn’t stop smiling.

The next few times this doctor saw me, he’d wink and ask if I’d remembered what that prick was called yet. I’d just shake my head, and refuse to answer. Later as my memory slowly improved I surprised him, by proudly announcing: ‘It’s Doris Bonson’. Thanks brain!

I can’t wait for the next episode. And I hope the doctor will appear again.

I’m most impressed that you remembered the prick! You were 100% correct on that one!

You are so talented. You write beautifully. And still manage to entertain in the midst of your hardship. Love you so much. Xxx

Well done Stewart. So interesting but scary. Please think about writing a book.xx

Thanks Aunty Lynn, it might take forty years at my current rate, but I’m getting there. Xx

Love it bro. U r a soldier. X